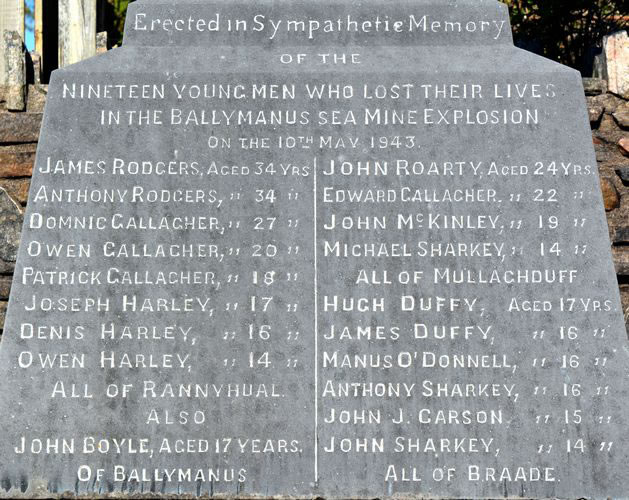

On the evening of 10 May 1943, Donegal would experience a tragedy that would claim the lives of 19 young men, aged between 13 and 34 years old, some from the same family in the Ballymanus Mine Disaster. Samantha Bailie reports:

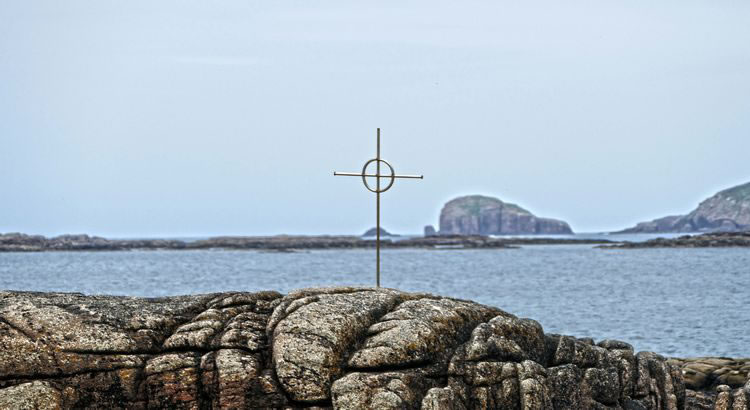

As the war ravaged Europe, a continuous stream of carnage was washed up on the shoreline of the Irish coast. Many of the battles fought in World War 2 were at sea and an important aspect of naval policy was the laying of sea mines. As we all know, the sea can be unpredictable and the current often distorted the direction of these floating mines away from intended targets and into areas they were not meant for. Unfortunately, one of these mines washed ashore in Ballymanus.

on closer examination and touch the top half of his body keeled over he had been severed in half by the blast.

On 10 May 1943, word spread around the area that a strange looking object was afloat in the water. With nothing much to do and with a general air of excitement Twenty-three young people went to have a look and described it as a mine, approximately 8 foot high with spikes facing down the way, suggesting it had been bent by the rocks and sea. As boredom set in, a sense of bravado prevailed Some of the group thinking the mine must be safe got a rope and decided that the best course of action would be to lasso the mine by the spikes and pull it to shore. This was the worst thing that could have happened – the mine exploded with a bang that could be heard 40 miles away.

People were stunned, and when the dust settled, the gruesome facts became evident – many had been killed outright, some were dismembered, while one young lad appeared just in a state of shock stood against the rocks however on closer examination and touch the top half of his body keeled over he had been severed in half by the blast. Some died later in hospital and only four survived. Nineteen males ranging from thirteen to thirty-four years old lost their lives.

From the documentary ‘The Ballymanus Disaster’ (or ‘Tubáiste Bhaile Mhánais’), presented by Donall Mac Ruairí we obtained a personal account when Michael Hanley, an interviewee, who told his story, and we could see that the aftermath of this tragedy still resonates within him deeply to this very day. He told how he was working in Scotland and his two young brothers were down at the shore collecting seaweed when the blast ricocheted through the air. He recalled how their father ran from the house, in only his slippers as he knew instantly that something awful had happened, and was met directly with the dreadful news.

Most of the dead were breadwinners supporting their families and grief left no house untouched, as a home either had a death or was grieving for close friends.

The dead were waked together and as mothers and fathers and brothers and sisters mourned in the local hall, Father McAteer, the local priest stunned the locals, he hit a coffin with his blackthorn stick, and told the grieving to “have sense” and instructed mothers to stop crying. Many locals viewed this behaviour as unacceptable – especially from someone who should have been offering words of comfort at that time.

Many people in Ballymanus are angry to this day that despite the local authorities and An Garda Síochána being made aware of the mine, no action was taken whatsoever to isolate the area until the mine was rendered harmless. There was plenty of time before the locals finding the mine that could have been used to deactivate it – this time was not used and this negligence resulted in death and devastation for many families.

A local man, Jim Duggan gave evidence afterwards that he spotted the mine at 4.30pm and went out in a currach to have a closer look. When he knew it was indeed a mine, he went to the post office at Kincasslagh and rang the Gardaí in nearby Annagry to report it. Gardaí received the call at 6.45pm and the Garda in charge of the station was Sergeant Frank Allen. His response was to send a message to the local coastguard, Morgan Dunleavy, asking that he go and check it out. Lieutenant Dunleavy drove the couple of miles to Ballymanus Strand on his motorbike and was aware that there was in fact a danger.

It was 8pm when he sent his brother to confirm to the Gardaí that it was a mine and he asked the crowd to withdraw while they waited for the arrival of the authorities to clear the area – however, only a few left, the rest stayed at the scene, not paying any attention to the coastguard, possibly not realising just how dangerous the mine was (probably because it had floated in and out a few times and even hit rocks without anything happening). When Dunleavy left the scene, some of the older men decided to pull the mine in themselves. This was both naïve of locals and negligent on the part of local authorities.

Locals called for an inquest and it was concluded with the jury that nineteen victims were killed by an exploding mine. They disagreed however as to whether Morgan Dunleavy was negligent but added a rider, which stated “We find that the disaster could have been avoided if Sergeant Allen had cordoned off the immediate vicinity of the mine until the arrival of the military.” Allen was not at the inquest but had been transferred the day after the explosion and was never seen again.

The late Tom Breslin who represented the then Taoiseach at the community hall in Mulduff acknowledged that the relevant authorities did not take the required measures when the mine’s arrival was brought to their attentions. There are an abundance of documents relating to the period which plainly indicate that once a report was provided to Gardaí that a mine was coming onshore that they were responsible to ensure the area was cordoned off.

One such document stated that “Whenever a report that an explosive article has been washed ashore is received at any Garda station the member-in-charge will immediately take such steps as are necessary to ensure that no one approaches to within 500 yards of the article and will at once report the matter to the nearest military post.” This mine was reported well before it exploded yet Gardaí did nothing to safeguard the public.

If very little was done at the time, it is painfully distressing to those relatives still alive who believe that there has been a huge cover-up since. Many surviving relatives feel that a state apology is necessary but it has not been forthcoming (perhaps the state fear compensation costs?) Surely it’s the least they deserve. Prominent locals and senior government figures have evidently ensured that the full facts of the incident would never immerge.

In 2008 an attempt was made to raise the issue at government level through local representative Senator Brian Ó Domhnaill. Although a reply was given and the state expressed their condolences to the families, an apology was not given. An admission of guilt and the state’s acceptance of blame would provide a measure of closure for some families but it seems it will not be forthcoming.

Senior Gardaí and government officials blame Sgt. Allen, the locals blame him and Allen himself stated “I see from the circular that it would be my duty to go to the scene – my only excuse for not proceeding to the scene was that I was awaiting word from Dunleavy.” It is clearly Allen’s inaction that was to blame – so why is there any confusion regarding the state’s responsibility towards the relatives?

With Allen admitting that he did not perform his duties effectively why was there no independent enquiry?

It was “ridiculous to hold an enquiry that would only show up the local people as an ignorant, stubborn lot who had no respect for authority.”

On a letter dated 15 May 1943, (just 5 days after the mine disaster and one day after the funerals) it read that there was no need for an independent enquiry! The letter was even approved and signed by Gerald Boland, the then Minister for Justice – the decision therefore not to have an independent enquiry was taken at the highest level of government, without the families affected being made aware of such a decision!

Did the relatives not know? Something quite odd happened – relatives changed their minds about an independent enquiry at a meeting that was attended by clergy and solicitors, where they decided unanimously that they would no longer demand an enquiry. This seems very strange – if not almost impossible – why would they change their minds? Perhaps a briefing letter from the local superintendant to the Gardaí Commissioner in Dublin illustrates the thinking behind such a decision. Breslin stated

It was “ridiculous to hold an enquiry that would only show up the local people as an ignorant, stubborn lot who had no respect for authority.”

Had the locals been ‘brainwashed’ in a sense into believing they would be seen nationally as a laughing stock? Had they been talked around and shown the ‘error of their ways’ in bringing attention to the area by being made to believe they had behaved in an anarchical manner? There was talk that three of the victims were in The White Army (a local gang of delinquents) – had the priests and solicitors told the locals that this would reflect badly on them as a people? However their silence was gained, they knew not to push the enquiry any further.

Looking back it is hard to believe that such a tragedy happened in the way it did but times were different, youth, boredom, naivety and communication lines that were less than efficient all played a part in this horrific and tragic loss of young lives.

Many thanks to Keith O’Grady of Brassneck Productions Ltd and Dearcán Media CIC for his tremendous help, and without whom, this article could not have been written.

Sites linking to this page have chosen to adopt this Privacy Policy as their own. This means: they agree to abide by the principles laid out below.

In common with other websites, log files are stored on the web server saving details such as the visitor's IP address, browser type, referring page and time of visit.

Cookies may be used to remember visitor preferences when interacting with the website. Where registration is required, the visitor's email and a username will be stored on the server.

The information is used to enhance the visitor's experience when using the website to display personalised content and possibly advertising.

Email addresses will not be sold, rented or leased to 3rd parties. Email may be sent to inform you of news of our services or offers by us or our affiliates.

If you have subscribed to one of our services, you may unsubscribe by following the instructions which were included in the email that you received.

You can block cookies via your browser settings but this may prevent you from accessing certain features of the website.

Cookies are small digital signature files that are stored by your web browser that allow your preferences to be recorded when visiting the website. Cookies are used by most websites to record visitor preferences. Also they may be used to track your return visits to the website.

Like all sites, we use 3rd party tools to help us run the website. They are used not to track you but to track info like the visitors numbers on the site over a given period, to allow you to interact with the social-media widget and to allow us to login into this web based CMS (Content Management System).