On 19th April 1940 Hannah Doherty, a 26-year-old single woman was last seen alive, but the story that would unfold following her death would include incest, adultery, pregnancy and insanity. Samantha Bailie reports:

Hannah Doherty was sitting at the fire with her parents, brother and local boy exchanging stories and eating supper. At 9PM the 26-year-old got up from her chair and left the house. Her parents didn’t think anything unusual in the fact she didn’t put on a coat or a hat, as she was a creature of habit and always visited an elderly neighbour by the name of Sarah Logue at this time, and seldom found the need to wrap up as it was only a stone throw from their house.

As 10:30PM came and went, Hannah’s parents began to worry; they knew their daughter’s routine and knew she always arrived home on the dot, so her mother left the house in hast shouting her name as she ran. Fifteen minutes later, the mother came home in a state as she had a gut feeling something must be very wrong, so to appease his frantic wife, the father said he would come and help track her down, but was convinced there was nothing to worry about.

The frantic parents searched all night, hardly believing she had simply vanished.

By sunrise the guards were called and the hunt stepped up a notch. At 3:20PM Mr. Doherty looked at an area he had previously explored, and what he saw barely registered, as his body temperature suddenly dropped – his beautiful daughter’s body was lying face down and fully stretched out. She had been beaten savagely around the head and ironically was less than 300 yards from her home.

When the guards were alerted they quickly found bloodstained stones and a hairnet 157 yards from the Doherty home. This illustrated that she had first been attacked there and then dragged (or carried) 130 yards to where she was murdered.

When the state pathologist Dr. McGrath was called to the scene, he was shocked by the barbarous nature of the crime – and no one in Ireland had seen more murder victims than he, which made his description of the wounds as “unusually savage” an indication to how severely Hannah Doherty had been battered. McGrath stated that the young lady had received 16 injuries to the head – indeed her skull had been smashed, but despite the severe beating, it was evident that someone’s hands had strangled her. Tests determined that Hannah had been killed between 9 and 10PM – but a piece of news that sent shockwaves through the family and community was the fact that Miss Doherty was forty days pregnant.

Gardaí went around the small community taking statements, and the night following Miss Doherty’s murder they called upon a man by the name of Daniel Doherty. Daniel was 29 and the youngest of 16 children. He was the only sibling left in the family home with his “ancient” mother, which he shared with his wife of six years, Ellen. Daniel worked his mother’s 20-acre farm where they grew potatoes, oats, turnips, had a couple of cows, a dozen or so chickens and a horse.

Hannah and Daniel were second cousins and in modern language “hung out” together on a regular basis, in fact Hannah’s parents had spoken at length about the unsociable hours of the night that he would appear at the house.

As the guards took Daniel’s statement, they noticed that he was acting very oddly, and more bizarrely, he wouldn’t stop drinking water. The guards didn’t know what to think – had his cousin and close friend’s death hit him so badly that he was finding it hard to cope? The guards asked Daniel where he was between 9 and 10PM and he replied that he had left the house of a friend. He then said he had went straight home and took his sick mare for a walk up and down the road, where he stated he had met a friend called Cassie McLoughlin who had called to their house just before 10PM.

Gardaí were suspicious – somehow Daniel had talked a good talk, but there was no real proof where he was between 9 and 10, and the guards felt that he had ample time to walk to where Hannah was killed – they estimated it would have taken him 17-20 minutes – so he could have killed her and been back at his house shortly before 10 when he met Cassie.

As Gardaí continued their enquiries, further information came to light, which, on 26 April led them to charge Daniel Doherty with the murder of his cousin Hannah – but was he the killer? Why would a man who spent great chunks of his time with his cousin suddenly want to take her life?

Daniel’s defence logged two pleas – one that he didn’t do it and the second that if he did, he was insane.

Although arrested in April, Doherty’s trial didn’t open until 26 November 1940, as there were great doubts about his mental health. The prosecution claimed that Daniel had got his cousin pregnant and had arranged to meet her on that fateful night, killed her and went home. Daniel pleaded his innocence, stating that he had gone straight from the house of a man called Douglas (who corroborated this) to his own house to take care of a sick horse.

One witness provided a direct link between Daniel and Hannah’s unborn child - he was Dr. McLoughlin, medical officer at the Malin Dispensary who stated that on 7 April Daniel had called him and asked for a bottle of medicine for a girl “who was in trouble with a soldier”. The doctor refused and Daniel was apparently “annoyed.”

The prosecution established that Daniel had killed Hannah: his close relations with her, the visit to the medical officer and his inability to account for himself at the key time when she was killed all pointed to him – however, establishing guilt was a whole new ballgame.

Daniel’s defence logged two pleas – one that he didn’t do it and the second that if he did, he was insane and therefore not responsible. Several witnesses were called including Warder Mahon from Sligo Prison who claimed he was “very restless” and complained of “violent pains in the head.” Another witness, a medical officer at the same prison claimed Daniel was not insane, as some people had stated.

Another witness stated that Daniel had “a high and narrow palate” which apparently meant he had a predisposition to insanity!! Dr. Dunne from the local mental hospital felt he was incoherent and could hear voices. Fellow prisoners claimed he talked normally to them but when an authority figure appeared he would act crazy, so Dr. Dunne labeled him “a malingerer” and said he felt he was simply trying to evade punishment and was fit to stand trial.

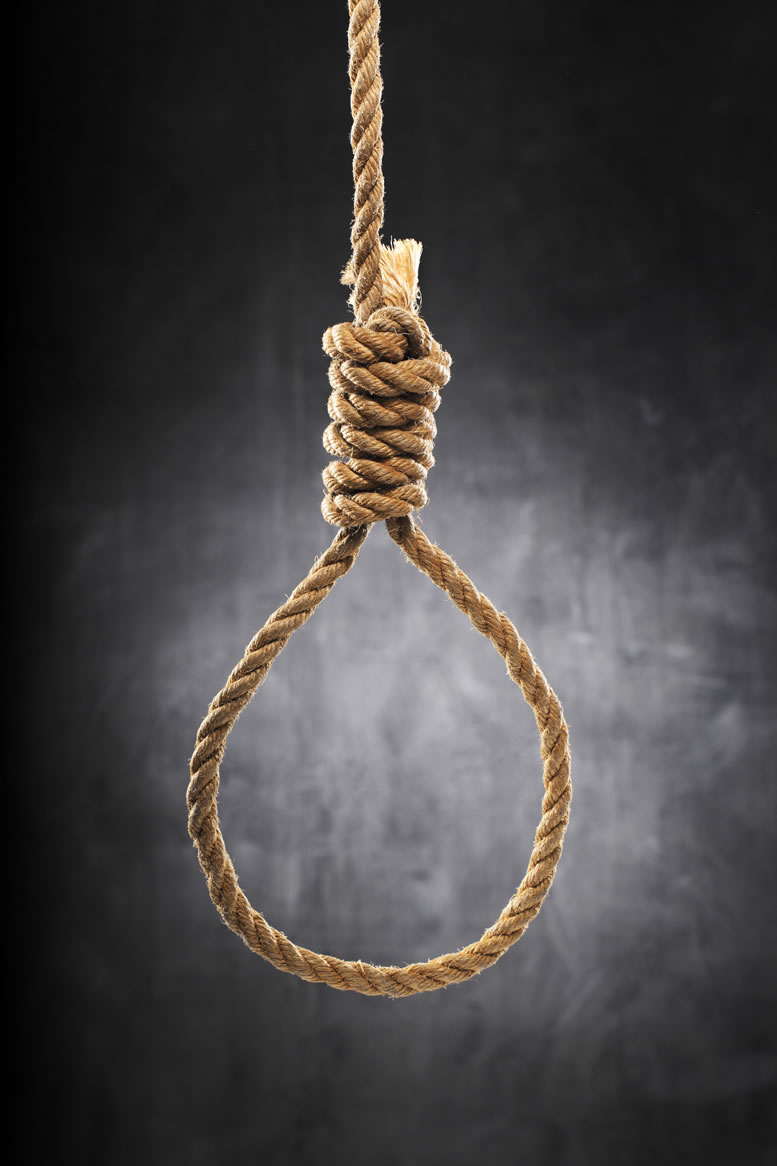

The defence of insanity was recognized in court and had previously been put forward in a few cases, however, while many of those executed were regarded as abnormal, there was only one who put a strong guilty-but-insane defence forward, and that was Daniel Doherty. The jury however were unimpressed and he was found guilty was hanged on 7 January 1941.

* Highly recommend ‘Hang for Murder’ by Tim Carey – Collins Press

Sites linking to this page have chosen to adopt this Privacy Policy as their own. This means: they agree to abide by the principles laid out below.

In common with other websites, log files are stored on the web server saving details such as the visitor's IP address, browser type, referring page and time of visit.

Cookies may be used to remember visitor preferences when interacting with the website. Where registration is required, the visitor's email and a username will be stored on the server.

The information is used to enhance the visitor's experience when using the website to display personalised content and possibly advertising.

Email addresses will not be sold, rented or leased to 3rd parties. Email may be sent to inform you of news of our services or offers by us or our affiliates.

If you have subscribed to one of our services, you may unsubscribe by following the instructions which were included in the email that you received.

You can block cookies via your browser settings but this may prevent you from accessing certain features of the website.

Cookies are small digital signature files that are stored by your web browser that allow your preferences to be recorded when visiting the website. Cookies are used by most websites to record visitor preferences. Also they may be used to track your return visits to the website.

Like all sites, we use 3rd party tools to help us run the website. They are used not to track you but to track info like the visitors numbers on the site over a given period, to allow you to interact with the social-media widget and to allow us to login into this web based CMS (Content Management System).